The

above statement aptly sums up Emitt Rhodes' self-titled debut, released

when he was just 20 years old. As Daniel Silverman argues on his Music

Base website, the album "is perhaps the purest pop confection ever

created." The albums that followed it were not exactly slouches. So, what

happened? Why haven't this music and the man responsible for it received

the recognition they deserve? There are a couple of likely reasons —

unfortunate circumstances and business moves — that contributed to

the present state-of-affairs. But before we examine these, let's take

a look at Emitt's musical career leading up to the Dunhill albums.

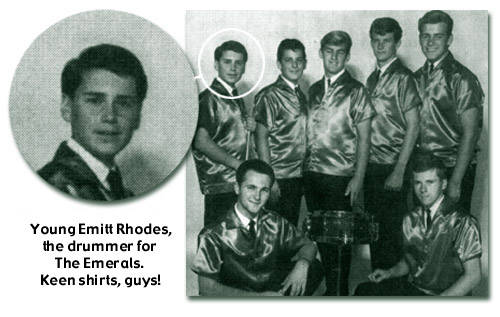

Born

February 25, 1950, Emitt Rhodes first made his mark on the Hawthorne,

California music scene as drummer for The Emerals. Various sources,

including the liner notes of "Listen, Listen: The Best of Emitt Rhodes",

refer to the band as the "Emeralds". It was, in fact, The "Emerals." As

John Gardner, a member of the band, recalls:

"Notice

that I said Emerals, not Emeralds. When we all picked names it did become

Emerals. We thought it sounded more exclusive than Emeralds at the time

(1964), so we dropped the 'D' on the end. I asked Emitt why it had said

Emeralds on the CD ["Listen, Listen" compilation], and he

said he really didn't remember 35 years ago! Truthfully, I am vague

too. However, I do have one of the original band cards and a newspaper

clipping with 'Emerals' on it."

(Click

here to see the newspaper clipping John mentioned. Cool little piece

of Emitt history!)

Along

with Emitt and Gardner, the band was comprised of brothers Don, Dave and

John Beaudoin, Bill Leeder and Dennis Troll. The band wasn't around for

long, though. In 1964, due to a contract dispute, a fifteen year-old Emitt,

John Gardner, and Bill Leeder decided to part ways with the group. (Gardner

still remembers the three of them coming to this decision while sitting

in a Winchell's Doughnut shop on Hawthorne Boulevard!)

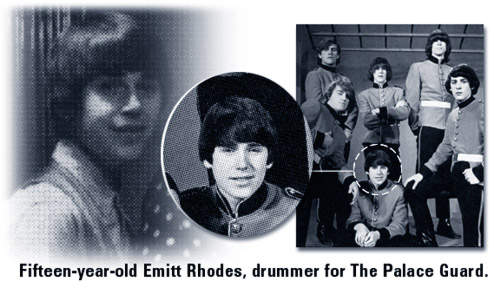

Apparently,

Emitt had a change of heart and reconciled with the other band members.

After growing their hair out and bringing in a few new members, they rechristened

themselves The Palace Guard. The following excerpt is from the booklet

that accompanies Rhino's box set "Nuggets: Original Artyfacts From the First

Psychedelic Period" (which features the group's single, "Falling Sugar"):

"Victims

of acute Anglophilia, The Palace Guard decked themselves out in red

British guardsmen's uniforms (wisely foregoing the huge bearskin hats)...the

three Beaudoin brothers were natives of Montreal, Canada, but relocated

to Los Angeles around 1964. Though bereft of any discernible musical

talent, they didn't let that obstacle stand in their way, surrounding

themselves with teenage bandmates who did have some, including 15-year-old,

Emitt Rhodes. After months of rehearsal, the band sounded halfway decent

and were ready for their big break, which came when KRLA DJ Casey Kasem

invited them to perform on his local TV dance show, Shebang. Their recording

debut came in mid-'65, backing Don Grady (who played Robbie on My Three

Sons) on a song called 'Little People.' They then released two more

singles in their own right on Orange-Empire, before waxing their almost-hit

'Falling Sugar' in early '66, a catchy Moptop-ish toe tapper brimming

with youthful fervor."

"Falling

Sugar" did fairly well locally, and The Palace Guard landed the job of

house band at the Hollywood nightspot, The Hullabaloo. There, Emitt really

got a chance to polish his skills as a drummer. Occasionally, the band

would even let him come out from behind his drum kit to sing a dead on

rendition of "Michelle."

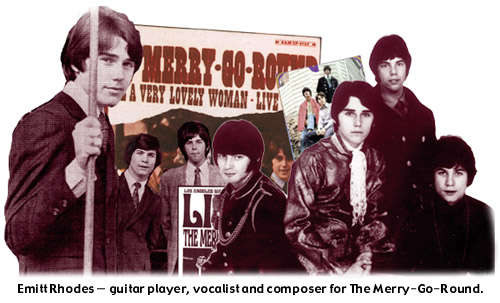

But Emitt was itching for something more. He had clearly been bitten by

the "Beatles-bug" and, in 1966, left The Palace Guard to form his own

four-piece, The Merry-Go-Round. In the process of changing bands,

he decided to change instruments as well, switching from drums to guitar.

"I learned how to play guitar," he explains, "because it was easier to

carry around...I wrote a song on a guitar that I had picked up —

it was my grandfather's or something — and I thought, wow, this is

fun! That led me to writing songs and playing the guitar, and that led

to The Merry-Go-Round, because I needed a band."

Emitt

and the high-school buddies he recruited to flesh out the group (Gary

Kato, Mike Rice and Doug Harwood) congregated in his parents' garage and

began the process of learning their instruments. As Emitt remembers, "I

had to get people who didn't know how to play so we could all learn at

the same time!" Eventually ex-Grass Roots drummer Joel Larson and ex-Leaves

bassist Bill Rhinehart were brought in to replace Rice and Harwood, at

manager Russ Shaw's suggestion. After rehearsing until they were comfortable

playing together, the group headed to the studio and plunked down $500

to record demos of two of their songs — "Live" and "Clown's

No Good."

"We

went to the studio with the idea that we were gonna demo... so we could

listen to it," relates Emitt. "We just went in and played it —

that was it. We didn't spend any time working on it. Nowadays,

you work on things. It was just pretty much live; we did work vocals

and then overdubbed the vocals. It wasn't like making a record today."

A&M

Records heard the demo of "Live" and decided to sign the band.

Gary Kato remembers; "We used the original demo of 'Live', but we beefed

it up after A&M signed us. We transferred it from the original four-track,

which we had recorded over at Western Sound Recorders about four months

earlier." The song was transferred to eight-track at Sunset Sound,

and the band laid down guitar and vocal overdubs to thicken up the sound.

A&M released the dressed-up demo as a single but wasn't prepared for

the song to do as well as it did. It quickly shot to the number one spot

in L.A.

The

previously-mentioned Nuggets box set also features "Live" and

the booklet weighs in on the song:

"Emitt

Rhodes and Gary Kato were still high school students in the L.A. beach

community of Hawthorne, California, when their first single 'Live,'

became a big hit in Los Angeles in early 1967. A classy piece of Southern

California-grown pop...The song's uplifting lyrics, rich, Beatles-esque

harmonies, and distinctive, swaying beat show a maturity and sophistication

few teenage garage bands could claim to possess."

"When

it started to make money," Emitt remembers, "and it was, like,

number one in L.A., the company said, 'Quick, let's put out product,'

So, they took the demos and mixed 'em all down and that was our album."

In late 1967, their debut album, The Merry-Go-Round was released.

The songs showed a group clearly inspired by the British beat bands —

particularly the Beatles — and Emitt's vocals drew strong comparisons

to Paul McCartney. Along with the Beatles influence, the songs featured

sprinklings of influence by other British bands such as The Who and The

Small Faces. There are also shades of The Byrds here and there —

not surprising, considering The Merry-Go-Round's base of operation. Of

the twelve songs on the album, Emitt was the sole author of ten of them.

He collaborated on an eleventh track, "Gonna Leave You Alone"

with Gary Kato, and the song is a fantastic example of Sixties garage-band

rock. With its driving beat and stinging guitar, the song is one of the

album's highlights and should have been a shoo-in for the Nuggets compilation.

The

fourth track recorded by M-G-R and featured on the album, "Time Will

Show The Wiser", featured a backwards guitar intro — a then

still-innovative technique. It was the first song to receive any actual

production. "It took us two months of sessions," Gary Kato remembers.

"Like the intro [guitar] line, Emitt and I did together, then took

the time to learn it completely in reverse, so that we could take the

tape, reverse the reversal, and get the original performance with a backwards

sound — a kind of sucking feeling. There's an overdubbed autoharp

played by our producer, Larry Marks. There were some guitar parts in the

middle section where we learned them an octave lower — slow —

and Bill Rhinehart and I played this slow pattern, which was then sped

up to regular speed, so it comes out sounding like teeny guitars.

We did the same thing to the piano part Larry Marks played. We went that

far. It was tricky stuff for the time." The Beatles influence was

becoming clearer and clearer. "We knew their albums inside out,"

Kato admits.

It

was nice to actually have an album out, but in reality it was nothing

more than a collection of dressed-up demos. Emitt had broader ambitions.

Again, he was itching for more. "After the album," he says,

"we then spent some time: we did overdubs, we thought about

it, the sounds got bigger. It was a Beatles trip. They were my favorite,

that's for sure. I like what the Beatles were doing because they seemed

to be the most innovative; actually they still sound pretty good.

Shit... they were hot."

It

was during this period that M-G-R recorded some of their finest work

— songs like, "Listen, Listen", "'Til The Day After,"

and "She Laughed Loud" (the last song saw Emitt foregoing his

typical McCartney-esque vocal approach to deliver a fairly convincing Lennon

impression.) "So, we were making singles at that point," Emitt

continues. "They were attempts at getting something that made some

money so we could keep our phony-baloney contract with A&M. And in actual

fact, they were all probably better than the stuff we had done before because

we actually spent some time in the studio."But,

as the Nugget's commentary continues:

"After

the success of 'Live,' A&M quickly rushed out an album, which revealed

Rhodes to be a gifted songwriter, heavily influenced by Lennon & McCartney.

The group went two-for-two when their second single, 'You're A Very Lovely

Woman,' also hit the top spot in L.A. But subsequent singles, though showing

Rhodes' rapid maturation, didn't sell as well. Relationships in the band

quickly became frayed, and after several lineup changes, The Merry-Go-Round

split up in early '69."

"Being

in a band is kinda like a marriage," Emitt explains. "It works

out for a while, then cracks start to develop. Rhinehart and I just didn't

get along. He was older, like 20. I wanted my way: 'I don't care if you're

bigger and older, I WANT MY WAY!' It all got to be a pain in the ass.

You spend a lot of time together, you get on each other's nerves, you

can't help it. There was no psychologist in the group; it was more, 'I

HATE you!' We used to spit in each other's faces, bloody each other's

noses. In the middle of the studio — can you imagine?"

They

were a fantastic band and deserved so much more recognition than they

received. However, after lasting just over two years, The Merry-Go-Round

was no more.

And

so we come to the much-loved Emitt Rhodes solo period. To avoid

the conflicts of personality and direction one encounters within a group,

Emitt decided that he would be better off as a one-man studio band. This

would allow him complete freedom and control over his musical vision.

He set up shop back at his parent's home. "When the Merry-Go-Round broke

up," he explains, "I bought myself an Ampex four-track — it

looked like a washing machine with big black knobs — [and] I put

it in a little shed my father had built behind the garage, and went for

it... I [had] three microphones, two microphone mixers — Shure microphone

mixers — and some amplifier speakers for monitoring purposes."

Emitt

assumed various roles simultaneously during the recording process. All

at once he would be the vocalist, musician, engineer and producer. The

first thing he would do is record a metronome set to the desired tempo

on one of the four tracks of his recorder. "I'd lay down a click

track," Emitt says. "a metronome, to keep a constant beat. To

set the tempo. Then on top of that I'd play the piano. Then I'd put down,

like tambourine and I'd combine that with drums. I'd put down bass and

I'd combine that with the rhythm guitar. Then I'd put down the lead."

He would have to record one instrument part at a time on the four-track

machine — laying down drums on one track, playing guitar on the next,

percussion on a third — then mixing them all down to the fourth track

so as to free up the first three for new parts. (The Beatles employed

the very same technique in the recording of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts

Club Band, among others, though they had the luxury of being four separate

musicians and having George Martin and Geoff Emerick to perform the more

technical tasks.) For Emitt, wearing all the hats, it was a very time

consuming process. "Then after I'd finished all the tracks, I'd transfer

them to an eight-track." The eight-track machine was one that he

rented and brought back to his studio. After transferring the instruments

from the four-track to the eight-track, he would lay down vocals on the

eight-track's leftover tracks. "It was not like today," he explains, "where

you have a separate channel for everything. I had to demo them first because

I had limited tracks. I would have to plan on what I did and where it

would go, so that it would mix correctly... I did a lot of stereo synthesizing

on the mixdown. I did all the stuff on the four-track and then took it

into Sound City with [former Music Machine bassist] Keith Olsen —

who wasn't rich then, just an engineer — and we split everything

up into multi-signals, filtered it all, and brought the kick drum back

up."

Earlier

in the recording process, Emitt had approached ABC/Dunhill with four instrumental

backing tracks — without vocals — and pitched his idea for a

one-man-band album. They liked what they heard and signed him to a solo

deal. "The first [album] I made with no money — Big Macs were

my staple. It was sold [to ABC/Dunhill], and I made $5,000 off of it.

I was rich. So I went out and bought more tape machines and more

microphones; there went the money. Then it was back to McDonald's again.

But I did move back into the garage — I needed a place to put my

grand piano."

With

the support of A&R rep Harvey Bruce, his album was given a home, and the

Producer credit was split between Bruce and Emitt. Also, receiving credit

on the album as mixdown engineers were Keith Olsen and Curt Boettcher

(As a side note, Boettcher was one half of the commercially unsuccessful

but now legendary sugary-psychedelic pop group Sagittarius,

the late-sixties studio creation that was the brainchild of producer Gary

Usher. They had a minor hit with the incredible single "My World Fell

Down" in 1967. Their only album, Present Tense, another overlooked

late-sixties pop gem, has miraculously been re-released on CD with bonus

tracks. Highly recommended. Keith Olsen would go on to produce

the mega-hit Rumours for Fleetwood Mac.)

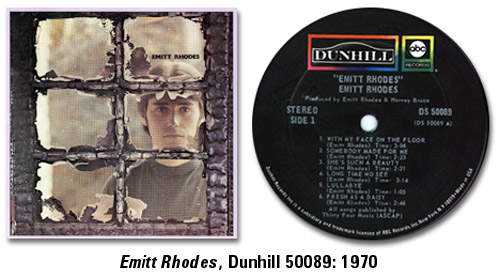

Released

in 1970, Emitt Rhodes is considered by many to be one of the most

overlooked and underappreciated albums ever. It is the kind of record

that literally got worn out due to repeated listens by the people who

did discover it. Few can deny the pop power of the album. Daniel Silverman,

on his wonderful Music

Base website, had this to say about the album:

"Intricate melodies and countermelodies, bass work this side of Abbey

Road, and the warm, recorded-at-home feel of the album add to the

air of quiet genius which is displayed in each track. The opening track,

'With My Face to the Floor,' sets the stage for astounding variations

on its simple and elegant Music Hall theme: straight piano-dominated

rhythms overlaid with understated drums, and acoustic and electric guitar

lines that, while not afraid to take the spotlight, never hog it. 'She's

Such a Beauty' and 'You Take the Dark Out of the Night,' are similarly

structured, involving deceptively simple rhythms and ornate vocal arrangements.

On the slower ballads, 'Long Time No See,' 'Live Till You Die,' and

'You Should Be Ashamed,' Rhodes never resorts to gimmickry or overarrangement,

instead demonstrating a precocious restraint for such a young studio-based

musician. Indeed, the arrangements, despite (or because of) their obvious

complexity, need no studio magic to embellish their effect; although

an element of insularity is inevitable in a one-man project such as

this, Rhodes makes no attempt to patchwork the recording with clutter.

Simple without being simplistic, touching without being cloying, Emitt

Rhodes is an unassuming masterpiece."

At

the time of its 1970 release, the album met with a warm response from

the critics and listeners. A few radio DJs lent the album a bit of mystique

and notoriety by implying (or blatantly claiming) that it was a new Beatles

record. (the Miscellaneous section of this site has a great example of

a DJ doing this very thing. Click

here to hear it.) And it did sound very much like White Album-era

McCartney, didn't it? Certainly, "Martha, My Dear" and "She's

Such A Beauty" could have been written by the same hand. Whether

anyone was fooled or not, the album began rising up the charts along with

the first single from the album, "Fresh As A Daisy." Everything seemed

to be going well for Emitt. He had made the music he wanted to make and

people were liking it. People were buying it. The album and single continued

to rise, but then the first of the previously mentioned setbacks arrived.

Back

in '69 when the Merry-Go-Round had disbanded, the group was still contractually

bound to provide A&M Records with another album. To fulfill this obligation,

Emitt had returned to the studio with a group of session players. He recorded

a few new tracks and completed some abandoned, half-finished M-G-R tracks.

The rest of the album was to be fleshed out with older, previously released

M-G-R tracks. It was to be, in effect, the last record by the Merry-Go-Round.

But it sat on the shelf at A&M, unreleased.

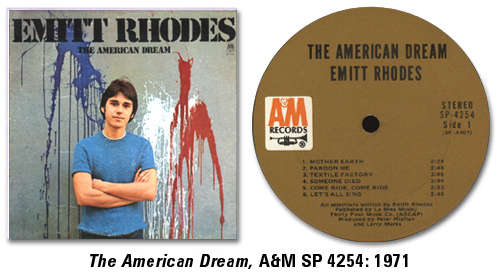

However,

once Emitt went on to secure a record deal with ABC/Dunhill and his debut

solo release started climbing up the charts, A&M saw an opportunity and

took it. They dusted off the shelved M-G-R album, renamed it The American

Dream and released it as a solo Emitt Rhodes album, pitting one solo

Emitt Rhodes album against the other. Buyers were confused. This was where

the first damage was done. Emitt feels that this one act of corporate

greed caused irreversible damage. "It definitely hurt sales, because people

went out to buy the record they heard on the radio, and they ended up

buying The American Dream."

Though

its timing may have been bad, by no means was The American Dream a

poor album. In fact, for Beatles fans, this album, along with Emitt

Rhodes, is essential listening. Emitt didn't seem pleased with it,

however, when talking about the album in 1970 prior to its release. "...Unfortunately,

... it had strings and horn parts that I just really didn't particularly

care for, but the producer felt it was necessary, so it went in."

It is a little puzzling that Emitt didn't care for all the Beatle-esque

embellishments of the songs, considering his penchant for the group and

his willingness to otherwise embrace their sound. The album contains some

classic Merry-Go-Round tracks such as "You're A Very Lovely Woman"

and "Till The Day After," but also quite a few new and previously

unreleased tracks which feature Emitt in some of his finer "McCartney-moments."

Songs like "Holly Park" and "In Days of Old," painted

in a vivid Magical Mystery Tour palette and chock-full of quarter-note

bounce, reveal Emitt to be Paul's long-lost musical twin. And Emitt wrote

few songs more beautiful and melodic than the haunting "Pardon Me",

with its hazy psychedelic "Fool On The Hill" flute/recorder

sounds. "Let's All Sing" is a happy little sing-along, most

notable for the fade out, in which, if you listen closely, you can hear

Emitt singing "All we are saying, is give peace a chance" in

the background. "Come Ride, Come Ride" — apparently intended

to serve as the centerpiece of a never fully realised M-G-R meisterwerk

— showcases Emitt at his psychedelic best, with layers of strings

and flutes swirling around the song's theme of a carousel (or as the album's

liner notes refer to it, the "great mandalla" or wheel of life.)

This number alone makes the album worthy of a reissue on CD. There are,

however, a couple of less-than-stellar moments on the album — moments

Daniel Silverman accurately describes as "...a mildly embarrassing

trek into Appalachia [Textile Factory], and a not-so-successful excursion

into calypso [Mary Will You Take My Hand]" — but overall the

album is a fantastic collection of pop music.

However

nice it may be to have these songs released, the album competed with Emitt's

newly created masterpiece, and as a result, Emitt Rhodes peaked

at #29 in early 1971. By all means a respectable showing, the album would

undoubtedly have gone higher without the release of The American Dream

thrown into the equation. The single, "Fresh As A Daisy," topped

out at #54. None of the other singles managed to chart.

As

Emitt put it, "A little glory in the sun, and then, boom, right back to

reality."

But

reality was even grimmer than before. It's hard to imagine now, but in

1970, artists were still expected to turn out two albums per year. Often

times, this was a contract stipulation. Such was the case with Emitt.

"Six months after I signed my solo deal, the contract was in suspension

because I hadn't given them another record," he explains. "I was

being sued...I was twenty years old when I signed my agreements. I don't

know what you were doing at twenty, but I wasn't a legal person, and I'm

still not. I was just making noise and playing and doing what I liked,

and I made this record." In one February 1971 newspaper article,

Emitt was interviewed during a six-night engagement at the Troubadour.

He explained that he liked performing, but was ready for the engagement

to end because it was "taking away from my studio time. I'm just upset

that I have to delay my second album."

But

even when he was in the studio, it was slow going, as the one-man band

production was still in effect. "I couldn't produce a record in six months

and have a life and like what I was doing. It was a lousy deal. It wasn't

as if I wasn't aware that it had taken me nine months to record the first

record and [that] six months was three months less. But I thought, well,

I made that first record. I can crank 'em out now [laughs]!" The pressure

from the label only made things harder.

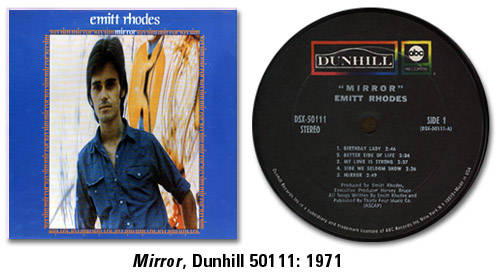

In

the end, it took Emitt almost a year to finish Mirror. While not

as thoroughly sparkling as its predecessor — the songs in general

are not as polished or developed as those of his debut — it is still

a wonderful record and definitely deserves to be rereleased on CD. In

the book 'Power Pop! - Conversations With The Power Pop Elite,' authors

Ken Sharp and Doug Sulpy interview Emitt. "...the difference between

Mirror and Emitt Rhodes," he explains, "was that

I actually started getting equipment then. I got a limiter. I got the

kind of things you can abuse." But he abused them well. Granted,

some of the tracks may have a slightly murky, squashed feel. However,

the songs are so good, they overcome these sonic shortcomings. Many of

the songs, such as "Better Side Of Life" and "Side We Seldom

Show," would have fit in perfectly on his first album (and in reality

may have evolved from older demos.) "Really Wanted You" is one

of Emitt's finest, most rocking songs, and the interplay between the guitar

parts is sublime (even more so when one bears in mind that he had only

been playing guitar for little over four years!) "That song is about

when I went and retrieved my wife from back East," Emitt says of

"Really Wanted You". "She was the flyer in some circus

act, and I got beat up. I'm not kidding. My wife went to replace somebody

in this act, she was a trapeze artist. I went and retrieved her, and the

catcher, the guy who catches the trapeze artist, got upset at me and beat

me up!"

Matthew

Greewald, a reviewer for All Music Guide, had this to say about the album:

"Following

the critical success of his debut solo album, Emitt Rhodes, the one

man Beatles, entered his home studio for the follow-up, and he did not

disappoint. Although not as cohesive as his last record, Mirror

is home to some of his finest material. 'Birthday Lady' and 'Really

Wanted You' are almost Stones-like in their attack, aggression, and

feel, and Rhodes pulls them off with fantastic results. 'Golden Child

of God' is also one of his finest compositions — it also would

have easily been at home on Paul McCartney's Ram. All in all,

this album is not a disappointment, coming off his self-titled debut,

Emitt Rhodes, which can easily be described as one of the classics

of the period."

Despite

the album's undeniable gems, it only managed to crawl to #182. Emitt suggests

that the album's poor showing was possibly due to the fact that his label

was more interested in his breach of contract than they were in promoting

the record.

Things

got even worse when his third album, Farewell To Paradise, failed

to chart at all. This aptly titled album had its share of decent songs,

but Emitt's musical focus had understandably shifted. Indeed, it seemed

as if he had undergone a sort of transformation. Gone was the clean cut

youth of days past; he had been replaced a more hirsute and moody-looking

Emitt, as the album cover showed us. And the liner notes more than hinted

at the turmoil he had been dealing with:

"If

gold is valuable because it is scarce, then sincerity must be even more

valuable because there is so precious little of it. I'm seldom attracted

to liner notes. I've only taken the time to read just a few. Those I

have, in so many words, praised whomever for his or her musical genius.

I find it difficult to do the same. If I possess a talent, it surely

must be patience. Someone said something about the world stepping aside

when a man knew what he wanted. I've known for some time and the world

hasn't made it any easier for me. Those things I cherish most I worked

long and paid dearly for. I am a recording artist, not just a songwriter

or musician. I have taken total responsibility of my art, avoiding the

temptation of using others to mask my weaknesses. My works are sincere

and entirely my own."

From

Sharp and Sulpy's book: "It was a conglomerate of everything I gleaned

from all the mistakes I made before. I thought that was probably my best

record and it was the record that I was least in contact with what was

going on in the rest of the world. By that time I had been isolated in

the garage for the longest period of time, but I was probably more in

contact with myself, so I got better and worse, all at the same time."

The

album showcases a wider range of sounds and influences, incorporating

at various times mellotron, saxophone, banjo and mandolin into its tracks

and finds Emitt experimentig more with time changes and rhythmical devices.

While virtually every song on his debut, Emitt Rhodes, would have

been perfectly at home on The White Album, Emitt had always maintained

that his influences were not limited to the Beatles, and he backs that

up on Farewell. The album has a few "McCartney moments"

(in particular "Only Lovers Decide" and the title track), but

it reaches well beyond them. Farewell To Paradise finds Emitt taking

a more hard-nosed, blues/rock-based approach to music, distancing himself

from the Sixties-pop mentality he had so skillfully mastered, and, unfortunately,

at times sacrificing much of the wonderfully developed melody and endearing

pop quality of his previous work. However, this makes those tracks on

which he does venture beyond standard blues/rock progressions and arrangements

stand out even more brightly.

This

album saw the return of the talented Curt Boettcher as mixdown engineer

and, perhaps as a result, sounds brighter and cleaner than Mirror,

on which Boettcher was absent. Emitt himself was also clearly learning

to get better sound with what he had and, by his own admission, was working

with better equipment than he had been previously. All of this lends Farewell

a slightly more modern and slicker sound than the previous albums.

One can definitely hear the "Seventies" seeping from the songs,

in both recording quality and content (maybe it's just the inclusion of

that ubiquitous Seventies saxophone in many of the tracks.) While I suppose

cleaner recording quality should generally be regarded as a good thing,

I personally prefer the slightly more lo-fi, homey pop quality of Emitt

Rhodes and Mirror. To these ears, the songs have a more organic

and warm quality than those on Farewell and, indeed, much of the

music that was released by the recording industry in the Seventies. A

clear example of the change in recording quality that occurred during

the Seventies can be had by comparing "Somebody Made For Me"

from the first album in 1970 to the unreleased 1980 Emitt track "Isn't

It So" from the Listen, Listen compilation. While it's always

nice to hear a new tune from Emitt, there is no question as to which of

these songs is superior, even though the latter track was recorded on

a twenty-four track machine with session musicians in a proper studio.

It's so slick and polished — nearly perfect — and a bit soulless

as a result (though I have to admit, that chorus gets stuck in my head

sometimes!) On the other hand, the 1970 song is perfect in its imperfection

— perfect in spite of its imperfection. There's just something

about the fact that it was recorded in a shed behind the man's garage

(his mom's garage at that!) and that he played all the parts

— sweating in deliberation over the details, innovating to make up

for his lack of technology — that helps make it a true pop gem (outside

of the fact that it is just a better song in general — not to make

less ot your later efforts, Emitt. I still want to hear the other two

tracks you recorded during the 1980 sessions. )

But,

I digress. Though tending toward a fairly different sound than the previous

albums, Farewell does make for good listening, and Emitt's skills

as a songwriter and musician are strongly evident. Says All Music Guide:

"This,

essentially Emitt Rhodes' third and final album, is once again a one-man-band

affair. It does differ, however, from his earlier efforts. The record

has a much more wistful, almost Harry Nilsson-like feeling, and this

permeates most of the cuts...Although not as buoyant as his earlier

efforts, Farewell To Paradise is still a very strong album, and

further cements his reputation as one of the great (albeit long-lost)

artists of the period."

In

the end, the album was overlooked and the label was after him. "After

that album, I stopped recording. I stopped writing because I was burnt

out. It was a lot of work, and a lot of trouble, to boot. The harder I

tried, the more trouble I was in. It wasn't rewarding anymore...I had

taken a much longer period of time to do the third album, and they were

suing me for more money than I had ever seen, and I just thought, why

do I want to do this?"

A

few shows here, a few shows there — Emitt eventually found himself

without a label, and his career came to a halt.

He

had had enough. He was 24.

EPILOGUE

The

strain and pressure of the record company breathing down his neck could

not have fostered the most creative of environments for Emitt's second

and third album. After the initial success of his incredible first album,

things had only gone downhill. His creativity and drive had to have been

affected by the strain caused by the legal situation he faced. He had

still managed to turn out albums with many wonderfully crafted and memorable

songs, but neither quite lived up to that brilliant 1970 debut masterpiece.

It is understandable, though, how the second and third album had a hard

time matching the glow of their predecessor. Few albums could. Created

in an atmosphere free from expectations and corporate pressure, the first

album had the vigor and immediacy of a twenty-year old musical tour-de-force

at the height of his game and with the whole world ahead of him. That

same prodigious force had crafted quite a few gems with the Merry-Go-Round

as well. It was his passion, it was his drive, it was his inspiration

that carried him forward. At some point, these were replaced by his obligation,

his contractual fulfillment, his breach of contract — destructive

things. And he eventually had enough.

So

it was probably with some small sense of relief that Emitt stepped into

obscurity, jaded at age 24. He had been burned by the business and decided

to play it safe. During the rest of the Seventies he spent most of his

time in the studio, not as an artist, but as a staff engineer/producer/pre-production

man and studio operator for Elektra/Asylum. A 1980 Emitt Rhodes return

album was started and then aborted when the A&R executive behind the project

left the label. Emitt laid low for a couple of decades, but the scenario

was repeated much more recently when an Emitt Rhodes album on the Rocktopia

label was planned for a 2000 release, only to be delayed and eventually

scrapped altogether when the label ran into some legal troubles.

Emitt

is still writing and recording, still in his garage studio. Now, however,

it's in his own garage, in the house he bought just across the street

from his parents house where he had recorded the Dunhill albums. It is

a far cry from those four-track days. His new studio is equipped with

all the modern necessities, from synthesizers and drum machines to digital

recorders.

"I'm

good at making noise," he says. "I'm a wonderful producer. I

should be doing it for a living. But I've never made big money off of

it — that's a talent, too. I've been in the garage forever. That's

how I got stuck in Hawthorne, because my studio was always there. I never

made enough money to buy myself a studio on the street. Actually, I never

had any desire to do that anyway — I'd much rather have it out back."

Emitt

still intends to release a new album in the near future. He's got thirty

years worth of demos and unrecorded songs hidden away in his studio. It's

only a matter of hooking up with the right people. Hopefully some day

soon we'll be blessed with another collection of songs from this long-lost

pop genius.

But

until then, crank up "Really Wanted You" or "With My Face On The Floor"

or "Listen, Listen" and revel in it. That ought to hold you for a while.

Hey, it's worked so far.

—

Obvious

thanks go to Michael Amicone and the liner notes that accompanied "Listen,

Listen: The Best Of Emitt Rhodes." I am also deeply indebted to Jennifer

DeBernardis for her incredible 1970 Emitt Rhodes radio recordings, Bud

Scoppa for the liner notes to "The Best of The-Merry-Go-Round,"

Matthew Greenwald and All Music Guide, Greg Shaw, Alec Palao, and Mike

Stax for the Nuggets liner notes, Ken Sharp and Doug Sulpy for their terrific

book "Power Pop! Conversations With The Power Pop Elite", Alan

Robinson for pointing out said book and for writing the liner notes for

the Edsel compilation, John Gardner for sharing his Emitt memories and

Emerals memorabilia, and Daniel Silverman for the wonderful Emitt commentary

on his Music Base website.

|